All about Git

🤔 The Problem

Imagine you’re writing a book. You save each chapter as a separate file:

- chapter1.doc,

- chapter1_final.doc,

- chapter1_really_final.doc,

- chapter1_final_v2.doc

Sound familiar? This chaotic approach is exactly what Git was created to solve.

At its core, Git is a distributed version control system. Think of it as a super-powered “track changes” for code, but one that doesn’t just track changes—it remembers everything, allows multiple people to work simultaneously without chaos, and lets you rewind time to any point in your project’s history.

Created by Linus Torvalds in 2005 (yes, the same person who created Linux), Git was designed to manage the sprawling Linux kernel development. Today, it’s the industry standard, used by nearly every software team on the planet.

The Three Problems Git Solves:

The “Final_FINAL” Problem Before Git, developers relied on manual backups, confusing file names, or shared network drives where someone might accidentally overwrite your work. Git eliminates this by creating a complete history of every change, who made it, when, and why. Every saved state (called a “commit”) is permanently stored, so you can always go back.

The Collaboration Problem How do five developers work on the same codebase without constantly breaking each other’s work? Git enables branching—creating parallel timelines of your project. Developers can work on features independently, then merge them together systematically. Platforms like GitHub and GitLab built upon this capability to enable global collaboration.

The “What Broke This?” Problem When something stops working, Git lets you pinpoint exactly which change introduced the bug. You can compare versions, revert specific changes, or explore alternative approaches in isolated branches without affecting the stable version.

Why You Need Git (Even If You Work Alone)

You might think: “I’m a solo developer, why bother?” Here’s why:

- Undo Anything: Accidentally deleted critical code? Git can restore it.

- Experiment Fearlessly: Try a risky change in a branch. If it fails, discard it without consequences.

- Document Your Progress: Commit messages create a narrative of your project’s evolution.

- Professional Preparation: Git is non-negotiable in tech careers.

The Bigger Picture

Git is more than a tool—it’s a paradigm shift in how we create software. By making version control accessible and distributed, it enabled the open-source revolution, transformed team workflows, and gave developers superpowers they now can’t imagine working without.

Whether you’re building the next big app, writing documentation, or managing configuration files, Git provides the safety net and collaboration framework that modern development requires. It’s not just for “coders”—anyone who works with files that change over time can benefit.

Version Control Systems: More Than Just Git

While Git dominates today’s landscape, understanding different types of Version Control Systems (VCS) helps appreciate why Git became the standard.

📂 Types of Version Control Systems: 1. Local Version Control System (VCS) 2. Centralized Version Control Systems (CVCS) 3. Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCS)

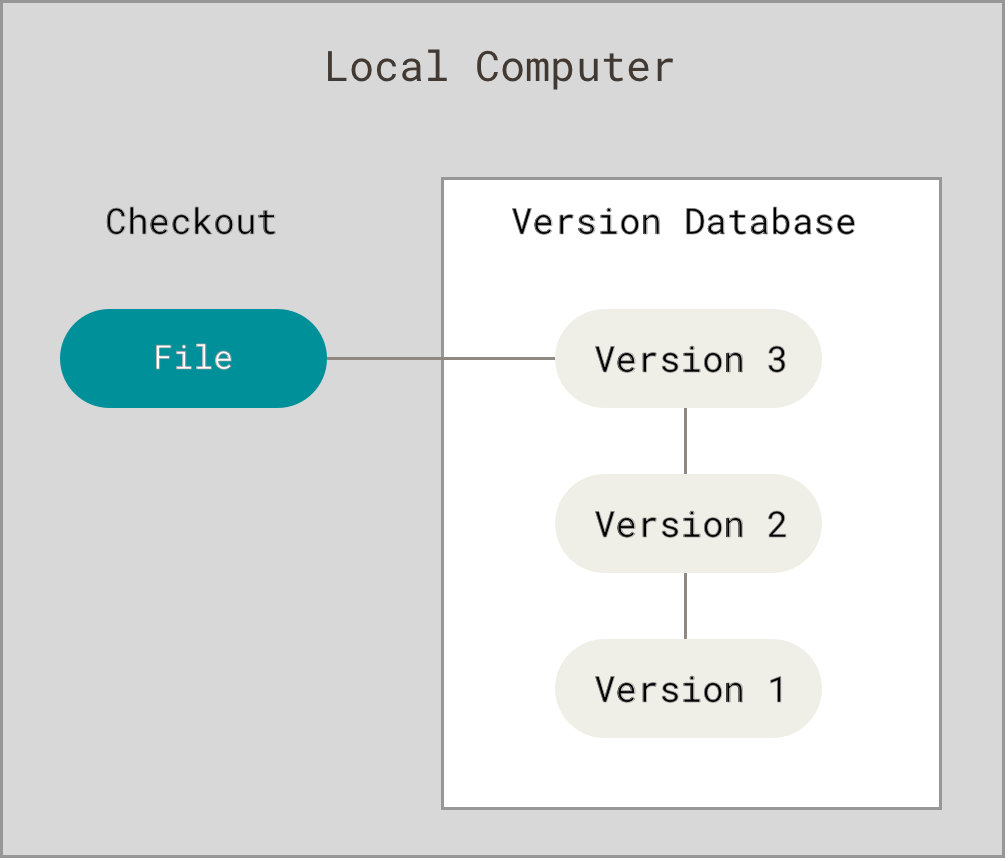

Local Version Control

The simplest approach where versioning happens on a single machine. A local version control system (VCS) operates entirely on a single machine, managing and tracking changes to files and projects within a local database. In this setup, all version history and modifications are stored directly on the user’s computer, without requiring a connection to a remote server or repository.

- Example: Manual copying (project_v1, project_v2) or tools like RCS (Revision Control System)

- Limitation: No collaboration, single point of failure.

Key characteristics of a local VCS:

- Self-contained: All data and functionality reside on the individual machine.

- Simple to set up: Does not require server configuration or network access.

- Solo development focus: Primarily suited for individual developers or small personal projects where collaboration and sharing are not a primary concern.

- Version tracking: Records changes to files as patches or snapshots, allowing for easy retrieval of previous versions.

- Limited collaboration: Sharing and merging changes with other users typically requires manual synchronization or external mechanisms, which can be cumbersome.

- Single point of failure: The entire version history is at risk if the local machine or its storage media fails, unless manual backups are consistently maintained.

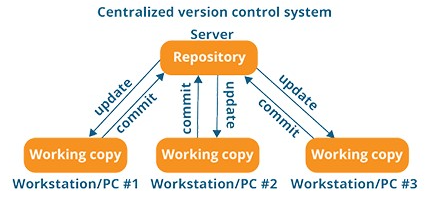

Centralized Version Control Systems (CVCS)

A centralized version control system (CVCS) is a system where a single, central server stores all the project files, their complete history, and manages all version control functions. Developers interact with this sole repository to get the latest version of files, make changes, and then commit those changes back to the central server.

Key Features

- Single Repository: There is one “source of truth” located on a central server that all team members access.

- Client-Server Model: Developers use client software to communicate with the central server, performing operations like “check out” (downloading files) and “check in” or “commit” (uploading changes).

- Access Control: Administrators can enforce fine-grained security policies and permissions from one location, controlling who can view or modify specific files and folders.

- File Locking (Optional): Some systems offer a file-locking mechanism to prevent multiple developers from modifying the same file simultaneously, which helps avoid merge conflicts, especially with binary files (like images or design assets) that are difficult to merge automatically.

- Network Dependency: A constant connection to the central server is typically required for most operations, including committing changes or viewing project history.

Examples

- Subversion (SVN): Often considered the most well-known modern CVCS, it was designed to improve upon the limitations of CVS and is still widely used in corporate environments.

- Concurrent Versions System (CVS): One of the earliest and most influential systems, though it is largely outdated now.

- Perforce Helix Core: A high-performance, centralized system that is popular in industries like game development due to its ability to handle very large files efficiently.

- Azure DevOps Server (previously TFS): Microsoft’s application lifecycle management solution which includes centralized version control capabilities.

Advantges and Disdvantages of Centralized Version Control System\

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Simplicity: Easier to set up, learn, and use than distributed systems, making it suitable for small teams or beginners. | Single point of failure: If the central server goes down, no one can commit changes, and data loss is a risk if not properly backed up. |

| Centralized Management: Provides a clear, single source of truth and simplifies administrative tasks like backups and user permission management. | Requires Network Connectivity: Most operations require a connection to the central server, hindering offline work or remote collaboration. |

| Good for Binary Files: More efficient for handling large binary files (which don’t merge well) because developers only pull the specific version they need, rather than the entire history. | Slower Operations: Reliance on network communication for every command can make operations slower compared to local operations in a distributed system. |

| Visibility: All team members have immediate visibility into the latest changes committed to the main repository. | Cumbersome Branching: Creating and merging branches can be more complex and slower than in distributed systems. |

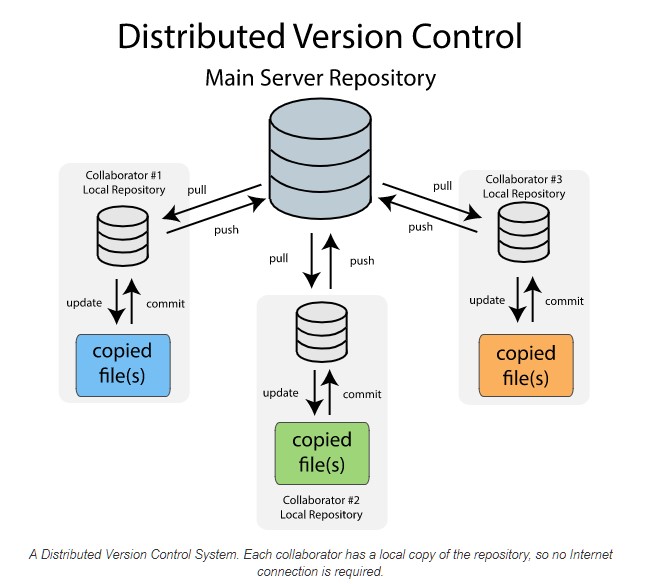

Distributed Version Control Systems (DVCS)

A distributed version control system (DVCS) is a system in which every developer on a team has a complete copy (or “clone”) of the entire project codebase, including its full history, on their local machine. This decentralized approach allows developers to work independently, offline, and without relying on a single central server for most operations.

The most widely used distributed version control systems include:

- Git: The dominant and most popular DVCS, known for its speed and flexibility.

- Mercurial: A cross-platform system that emphasizes simplicity and performance, similar to Git.

- Bazaar (bzr): A flexible system that supports both centralized and distributed workflows.

Key Concepts

- Local Repository: Each developer’s local copy acts as a full-fledged repository, allowing them to commit changes, view history, and create branches quickly on their own machine.

- Remote Repository: While work happens locally, teams typically use a shared “remote” repository (often hosted on platforms like GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket) to synchronize and share changes with others.

- Push and Pull: Developers use

pushcommands to upload their committed local changes to the remote repository andpullcommands to download updates from the remote repository to their local copy. - Branching and Merging: DVCS makes creating separate, independent branches for new features or bug fixes very efficient. Once a task is complete, the changes are merged back into the main codebase.

Advantages

- Offline Access: Most development activities, such as committing and branching, can be performed without an internet connection.

- Performance: Operations like commits, viewing history, and reverting changes are significantly faster because they interact with the local hard drive rather than a remote server.

- No Single Point of Failure: Because every developer has a complete copy of the project history, the data can be recovered from any local repository if the main server crashes.

- Flexible Workflows: DVCS supports various collaboration models, including the common pull-request workflow, where changes are reviewed and discussed before being merged into the main project.

Evolution of Version Control SysLoca’x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Local VCS (RCS)

│

▼

Centralized VCS (CVS, SVN)

│

▼

Distributed VCS (Git, Mercurial)

- Local → Track versions on one computer.

- Centralized → One server, multiple users.

- Distributed → Everyone has the full repo, enabling collaboration and resilience.

🎯 Why Git Became the Standard

- Speed: Local commits and branching are instant.

- Resilience: Every developer has the full history.

- Flexibility: Powerful branching and merging workflows.

- Community: GitHub and GitLab made collaboration seamless.

Git Architecture

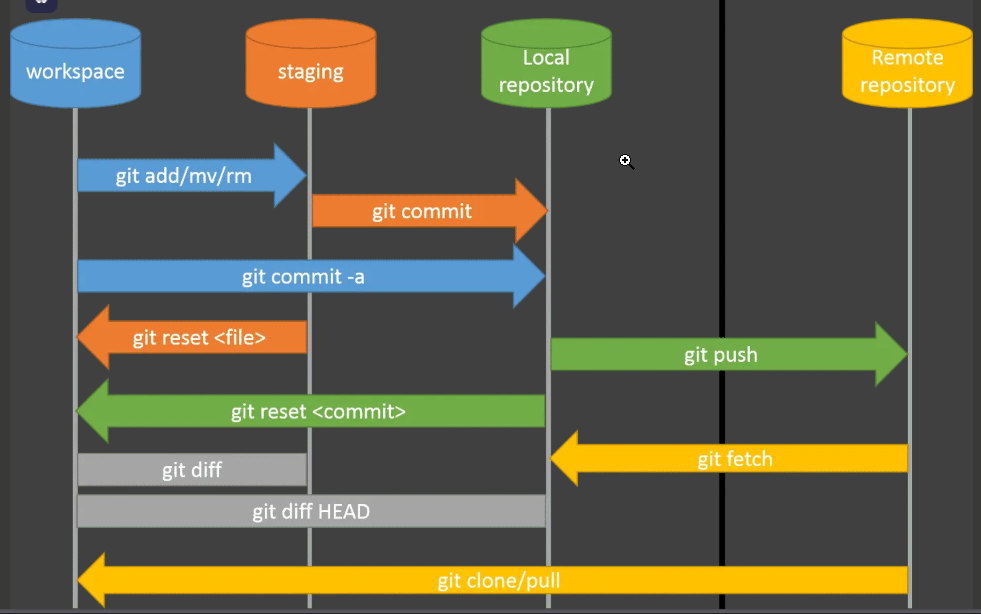

Version control systems typically operate on a two-tier architecture; however, Git distinguishes itself through a three-tier structure, incorporating an additional layer that contributes to its unique functionality and flexibility. This architecture comprises the working directory, the staging area, and the local repository.

- The working directory, established upon Git repository initialization, serves as the environment where developers can directly modify the source code. Subsequently,

- the staging area acts as an intermediate layer, allowing users to selectively stage changes made in the working directory using the git add command, providing a preview of the modifications intended for the subsequent commit. This staging mechanism ensures that only the desired changes are included in the next snapshot, and any further modifications in the working directory necessitate a re-staging process to synchronize the snapshots.

- Finally, the local repository serves as the permanent storage for committed changes, finalized through the git commit command, thereby preserving the project’s history and enabling efficient version management.

Git Workflows: Different Ways to Collaborate

Different teams use Git differently depending on their size, release cycle, and project complexity. Here are the most common workflows:

- Centralized Workflow

- Feature Branch Workflow

- Gitflow Workflow

- Forking Workflow

- Trunk-Based Development

Centralized Workflow

The simplest model, similar to SVN but using Git.

- Single main/master branch

- Developers clone the repository

- Work locally and commit to their local repo

- Push changes directly to main branch

- Resolve conflicts before pushing

Best for: Small teams, beginners, simple projects

Feature Branch Workflow

The Feature Branch Workflow is one of the most popular Git branching strategies because it keeps your main branch clean while allowing developers to work independently on new features.

🌿 Core Principles of Feature Branch Workflow

- Main branch stays stable. Typically main or master is always deployable and free of experimental code.

- Each feature gets its own branch. Developers create a branch off for a specific feature, bugfix, or experiment.

- Isolation of work. Changes are contained in the feature branch, so they don’t affect others until merged.

- Pull Requests (PRs). When the feature is ready, a PR is opened for review, discussion, and testing before merging.

- Merge back into main. After approval, the feature branch is merged into and usually deleted to keep the repo tidy.

Typical Feature Branch Workflow Steps

Start from main

1 2

git checkout main git pull origin main

Create a feature branch. Work on your changes. Commit regularly with meaningful messages.

1

git checkout -b feature/awesome-featurePush branch to remote

1

git push origin feature/awesome-feature

Open a Pull Request. Team reviews, runs tests, and suggests improvements.

Merge & clean up

1 2 3

git checkout main git merge feature/awesome-feature git branch -d feature/awesome-feature

A Real Project Examples

I’ll walk you through the essentials of Git using real examples from my System-Monitor-Dashboard-Plugin project.

🔹 1. Setting Up a Repository

Usually you start with an empty repo on GitHub.

- You create a new repo on GitHub (no files, just the repo shell).

- Then you link it with local repo.

- Finally, you push your local commits.

Start by initializing Git in your project folder in local pc:

1

2

git init

git remote add origin https://github.com/ZahidHasan/System-Monitor-Dashboard-Plugin.git

When you run: git init, Git initializes a new repository in your project folder. It will create a hidden folder nammed .git in your project folder. Without this folder, Git wouldn’t know how to track changes. So after , your project is now “Git-aware” — ready to track commits, branches, and history.

When you run: git remote add origin https: You’re telling Git:

- “This local repo is linked to that remote repo on GitHub, and I’ll call it

origin.” originis just a nickname for the remote URL. Now, when you push or pull, Git knows where to sync your changes. You Linking your local repo to GitHub.

Project Folder

│

├── code files (your plugin, README, etc.)

│

└── .git (hidden folder created by `git init`)

├── objects/ (stores commits, file snapshots)

├── refs/ (branch and tag pointers)

├── HEAD (current branch reference)

├── config (repo settings, remotes)

└── logs/ (activity history)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

┌───────────────┐

│ git init │

└───────┬───────┘

│

▼

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ Hidden .git folder created│

│ (stores commits, branches,│

│ tags, config, history) │

└───────┬───────────────────┘

│

▼

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ git remote add origin URL │

│ (link local repo to GitHub│

│ remote, nickname = origin)│

└───────┬───────────────────┘

│

▼

┌───────────────────────────┐

│ git push -u origin main │

│ (upload local commits to │

│ GitHub, set tracking) │

└───────────────────────────┘

Another way to start is that you create an empty repository on github then clone it into your local PC. In ths case you dont nedd to perform git init. .git folder will be downloaded from github. You then work as usual.

1

git clone https://github.com/ZahidHasan/System-Monitor-Dashboard-Plugin.git

git Pull vs git Fetch

git fetch is a safe command that updates your local copy of the remote branch (e.g., origin/main), but it does not modify your local working files or current branch. This allows you to: Review incoming changes before integrating them into your work. Compare the fetched changes with your local branch using git log or git diff to understand what’s new. Decide the best way to integrate the changes (e.g., using git merge or git rebase manually).

git pull is essentially a shorthand command for git fetch followed by either git merge (by default) or git rebase (if configured). This command: Automatically updates your local working directory to match the remote’s state. Is convenient for quickly synchronizing your branch when you are confident no conflicts will occur. Can lead to immediate merge conflicts if your local changes overlap with the remote changes, potentially disrupting your workflow.